It’s Friday evening. You’ve just launched well-tested Hadoop job which took you the whole week to create. You estimate that it will complete in couple of days. You navigate your browser to tasktracker and periodically click "Refresh page", while constantly watching at slowly increasing completion percentage. Everything seems to be all right. Being confident that the job will complete by Monday, you go home.

However, on Monday you discover that everything went south.

Logs reveal that events unfolded as follows.

A part of network with a number of Hadoop nodes went down at some point.

But this should not be a big deal because Hadoop is designed to be resilient.

It restarted failed tasks on other nodes.

This only would slightly increase running time of the job — just a minor nuisance.

Eventually all mappers completed successfully, and now completion time depends only on reducers.

Reducers worked hard for hours and almost all of them completed successfully,

except very small number of reducers which are still running and will be running for much longer

because they are only 70% complete, meaning that they are in the very beginning of reduce > reduce stage.

Seems that data is distributed unevenly.

Ten more hours have passed.

One of the slow reducers was killed because it had failed to send heartbeat in time limit.

If was restarted.

The progress of newly restarted reducer now is even worse than before:

it is stuck in copying output from the mappers.

Turns out that the disk where one of the mapper output is stored is nearly dead.

A couple of more hours passed.

Failing disk died permanently.

Hadoop had to restart mapper task, making slow reducer to stall because it needs output from this mapper.

At this moment you understand that the job will never complete successfully.

Various failures will plague your job until you give up.

Upset, you decide to read email and the very first message that catches your eyes

is from Hadoop support team stating that they are going to shut down the cluster in 12 hours

for scheduled maintenance.

This kills any remaining hopes of the job success.

You open terminal window and enter hadoop job kill ... command.

Sounds familiar? Long jobs are the classical error of designing bigdata dataflows. You managed to put all logics and all data into single large job which will work for hours and maybe even days. Instead, you should have split it into shorter jobs of 30-60 minutes each. At first glance, this idea seems against rational thinking. Reasons against:

-

Single large job adds only single entity to our dataflow. This means fewer lines of code, less testing, shorter startup and monitoring scripts. Such approach seems cheaper.

-

Single large job is IO-optimal: data is read from HDFS only once. A sequence of short stages would save results of intermediate stages onto HDFS, hence inevitably generating larger amount of IO.

But this is a mere illusion. Long jobs do not work. The longer the job works, the fewer chances it has for success. A series of short jobs of 30-60 minutes each will complete faster than single long job. For example, let’s assume that we have single large job which in perfect world completes in 10 hours. In perfect world, there are no hardware or software errors, input data is clean, cluster doesn’t require maintenance, and you never have urgent desire to change the code of the already launched job. Alas, perfect world exists only on paper. When this large job meets real world, it will take 50 hours for it to complete because of failures and restarts. On the other hand, accurately crafted series of short jobs would complete in 20 hours. This is the best you can do in real world.

The most important skill in bigdata — including Hadoop — is the skill to design dataflows consisting of short-running jobs. Short-running jobs are the key to stability, albeit at the cost of efficiency. Without stability, you won’t be able to create serious dataflows: you will be indefinitely stuck in job failures and restarts. Accept that efficiency is of secondary importance. All people new to bigdata do the same mistake by trying to put as much as possible code and to feed as much as possible data to a single large job. These by-the-book jobs always lose to the uglier, but practical, designs. The faster you accept that, the faster you will rule batch processing (and Hadoop in particular) and not vice versa. Typically sequence of practical, industrial-grade jobs generates 2-3 times more IO than "perfect" solution.

Let’s move on to examples. Below I will list some problems which, although can be solved in a straightforward way, must be decomposed into smaller parts if you want to achieve production-grade stability.

Imagine that we perform services in the field of social data mining.

Our primary dataset is a huge collection of messages (date, text) from various social networks.

Our current task is to create a report about some politician on how their rating changes day-to-day

over the course of the last five years.

Let’s assume that we already have a well-tested ML-analyzer that is able to detect for any given message

whether it relates to the person of interest and, if the answer is yes, it also computes

rating ranging from "very positive" to "very negative" based on the emotional analysis of the text.

For example,

"First step to cut unnecessary public expenditure: H.L.I. proposed to dim street lights"

would be rated positively,

while "I bet this moron H.L.I. doesn’t commute after nightfall" — negatively.

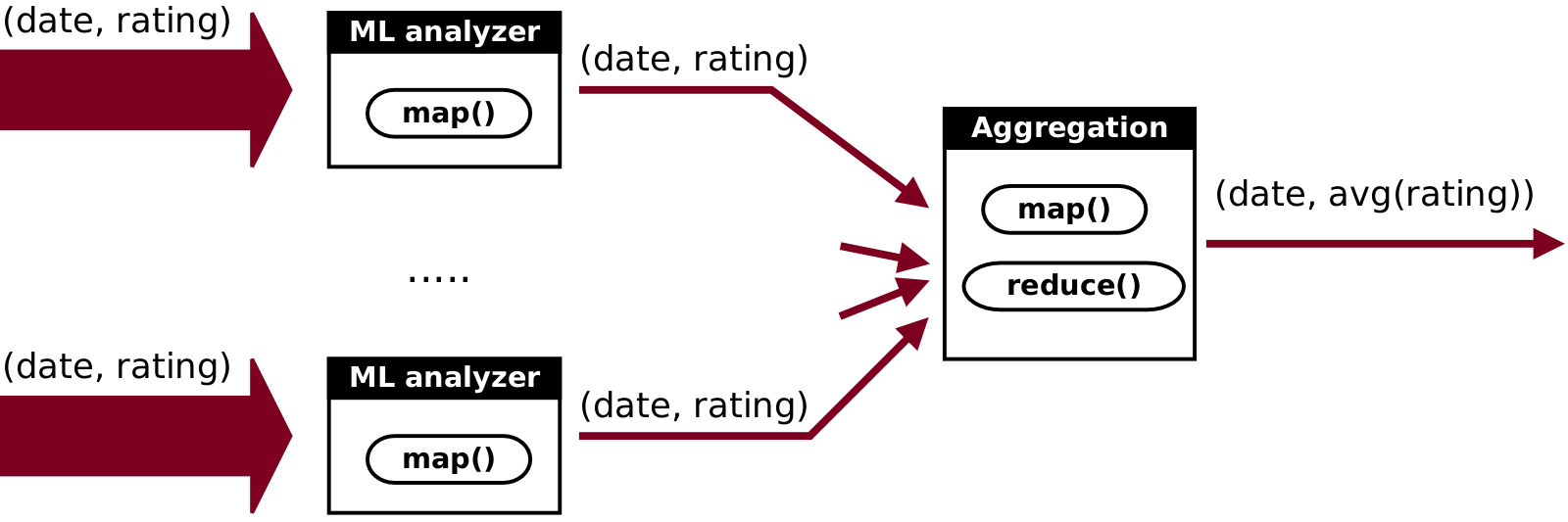

Straightforward solution is very simple.

We feed all historical data into the job.

Next we call analyzer in mappers for every post.

Analyzer returns either a pair of (date, rating) if it finds a reference to the person we are interested in,

otherwise it returns nothing.

Next we reduce all pairs by date.

Job outputs very small file with format (date, avg(rating)).

Unfortunately, if we feed 5-year data into such job, it will work for too long. We would put ourselves at risk because we wouldn’t be able to reliably estimate when results become ready. To be on the safe side, we can split the job into smaller ones. Our new dataflow consists of two jobs:

-

First job takes some amount of input data and applies analyzer. It doesn’t have reducers. Instead, it persists all emitted

(date, rating)pairs onto HDFS. We could use combiner/reducer to reduce number of pairs, but it is not worse of effort because total volume of pairs is negligibly small compared to the volume of input data. So, we won’t do that. We start this job multiple times, every time feeding some part of input data. We select volume size small enough for a single job instance to complete in 30-60 minutes. -

Second job takes all outputs of all runs of the previous job and performs reduction. Because pairs are very small compared to input text data, this job completes very fast even though it processes data from all previous jobs combined.

Total number of job instances is N+1. First N jobs can be run in parallel if cluster resources are plentiful.

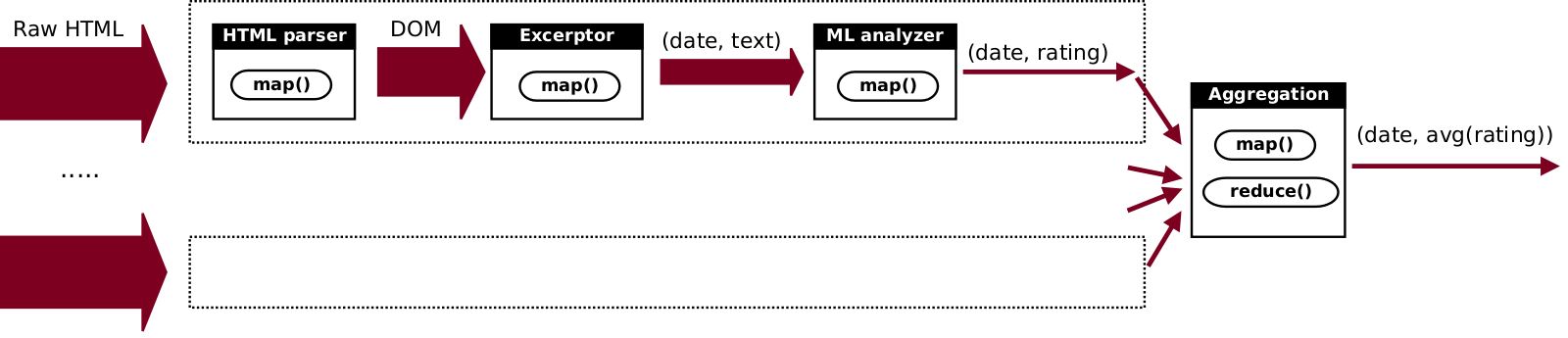

Now let’s make previous example a bit harder.

We are going to solve the same problem, but instead of tuples (date, text)

our input will be raw HTML pages from an assortment of forums, mailing lists and similar

sites hosting predominantly user-generated content.

Additional complexity arises from much more complicated logics involved.

First, we need to call HTML parser to convert raw HTML into a more suitable structure for analysis, such as DOM.

Next we need to apply algorithm that will extract independent messages (e.g. forum replies) from DOM tree as an

array of pairs (date, text).

Lastly, we need to call the analyzer from the previous example.

Note that the last two algorithms do not belong to "either it works or not" type.

Their quality is a quantitive metric.

As such, it would be natural to constantly improve these algorithms and, consequently, to rerun them.

We should keep it in mind when we design dataflow.

We start with the same solution as was described in the previous example.

We split input data into chunks of moderate size and process them independently.

After all of them are done, we launch final job to perform reduction by date,

which produces final output (date, avg(rating)).

The difference here will be in that we will process every chunk not with a single job,

but with a sequence of three smaller jobs:

1) parse HTML; 2) extract excerpts as (date, text); 3) apply analyzer to the text of each tuple.

Motivation for such design is that we don’t want to keep a lot of code in a single job.

We can freely modify (2) or (3) and rerun only later stages.

This will be cheaper than to rerun everything from scratch every time we modify these algorithms.

Total number of job instances is 3*N+1. At any given time, we can run N jobs in parallel (one job for every split).

Our third example will be even more complicated. Now we are going to solve a problem of global-wise map/reduce over huge dataset. In the previous examples, the number of reduce keys was only 365*5. Think about this figure as an exception because typical real-world jobs have number of keys proportional to the volume of input data. In extreme cases of graph analysis number of reduce keys can be of order 10^9. (It it noteworthy that map-reduce is not very suitable for graph analysis. Graph algorithms require random access to other elements of the graph. Trying to fit them into map-reduce framework produces disappointingly inefficient and cumbersome solutions. It is almost always better to use ad-hock C++ application in a dedicated server with enormous amount of RAM; or to use specialized distributed graph-processing software atop of low-latency network).

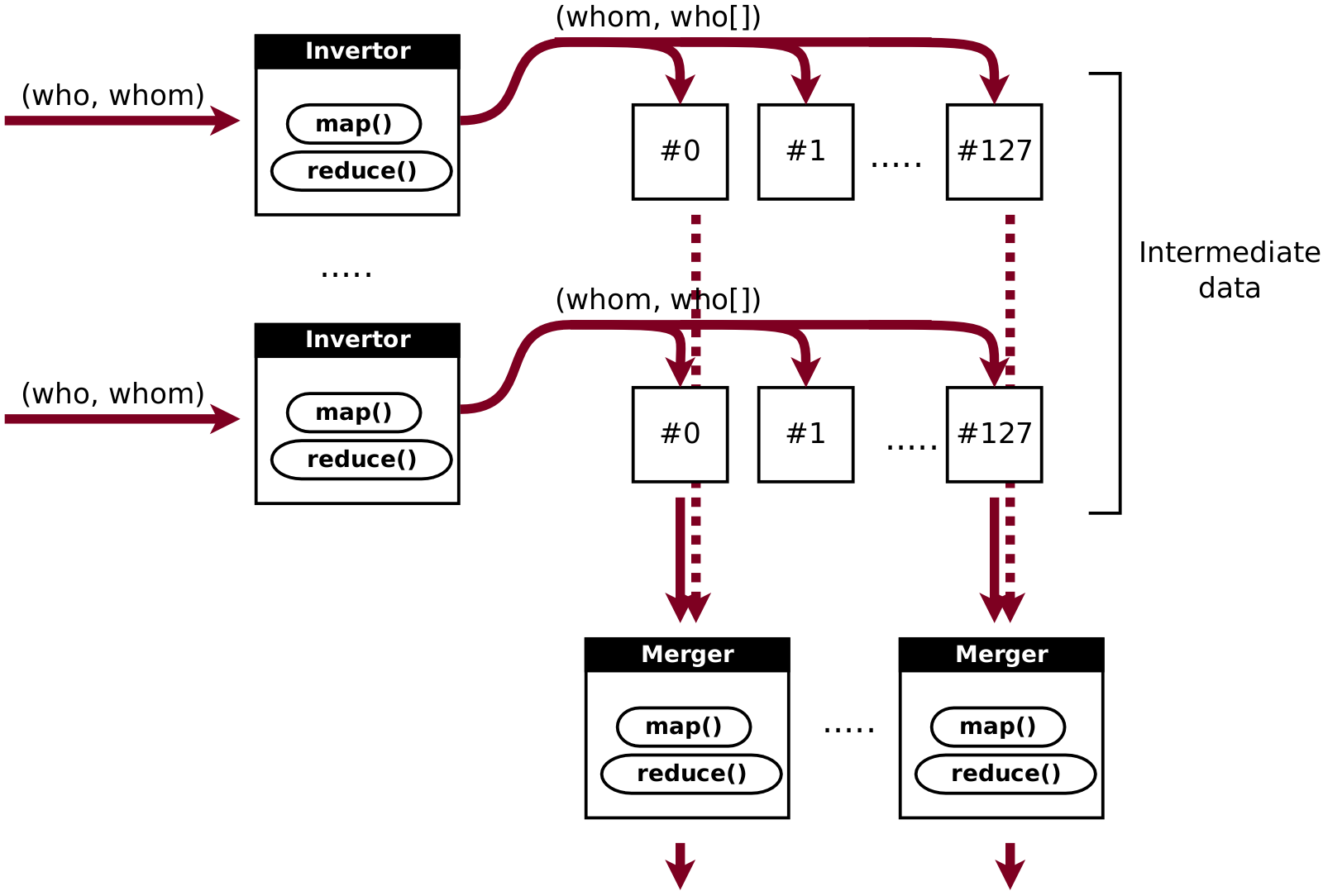

Let’s consider the task of building lists of followers in a social network.

Our input data contains pairs of followers in format (who, whom).

We would like to invert these pairs into (whom, who[]),

i.e. for every user to get a list of other users who follow him/her.

First obvious step is to split input data into chunks and to process every chunk individually.

Every such job (called invertor in the image below) will produce partial results (whom, who[]).

They are partial because who[] lists are incomplete.

To get full lists, we need to merge all such lists from all invertors for every whom key.

For example, if invertor #0 outputs (5, [3,6,10]), invertor #1 outputs (5, []) and invertor #2 outputs (5, [7,11]),

then the correct result is the concatenation of these partial lists: (5, [3,6,7,10,11]).

How can we do this?

We could do this in a single final job as we did in previous examples.

Alas, it won’t work nicely.

The reason is that invertors do not filter out any data as first-stage jobs in previous examples did.

The whole volume of data is promoted to the next stage.

As such, second stage will work for too long.

So, let’s split it into a number of merger jobs either.

We will do this by using mapreduce approach, but on a higher — job management — level.

Remember that every map/reduce job outputs not a single file but a fixed number of partitions,

equal to the number of reducers.

Let’s configure invertors to use the same number of reducers: job.setNumReduceTasks(1024);.

This ensures that partitions with different numbers contain strictly non-intersecting sets of keys.

Now we can perform merging "vertically", as demonstrated in the image below.

This completes our solution.

Total number of job instances is N1+N2. We first launch all N1 invertors and wait for their completion, then we launch all N2 merger jobs.

Now let’s put examples aside. There is another issue that significantly limits stability: the fact that running jobs affect one another. When there is only a single job running in a cluster, it owns all resources, including CPU, RAM, disk and network bandwidth. This makes running time fairly stable. For instance, if you measured empirically that you need 4 hours to process one day of historical data, then you can be sure that it will take the same 4 hours to rerun this job. But when there are multiple jobs running in a cluster (hundreds of jobs running simultaneously is a common situation in large clusters), resource contention begins. You cannot forecast now for how long your dataflow will run: sometimes it will take 4 hours to complete, sometimes — 6 hours and sometimes 10.

Luckily, in real clusters, CPU and RAM are strictly divided between task slots: every map and reduce slot gets single physical core and some fixed amount of RAM (1-4 GB). Otherwise it would be impossible to schedule multiple jobs in parallel. If there were no RAM limits, then sooner or later you would encounter OOM. If there were no CPU affinity, then smart developers would create jobs with multiple threads, thereby gaining advantage over others' jobs. Hence CPU and RAM are strictly divided and are not a source of resource contention. But disk and network still pose a problem. If there is only single running job in a cluster, then it gets all the bandwidth of both disk and network. But if there are many running jobs, then bandwidth is divided among all the jobs, resulting in any single job running for longer than when it was alone. So, here is word of advice: don’t rely on running time figures observed in an empty cluster (e.g. after restart). They are overly optimistic. If you want to get realistic values, measure running time in a fully-utilized cluster.

Summary:

-

Long-running jobs are prone to long sequences of failures and restarts, delaying completion or making it impossible

-

Stabilize them by decomposing them into shorter jobs of 30-60 minutes each, even at the cost of efficiency

-

If this is not possible, multiply projected completion time by large factor to compensate for almost certain failures